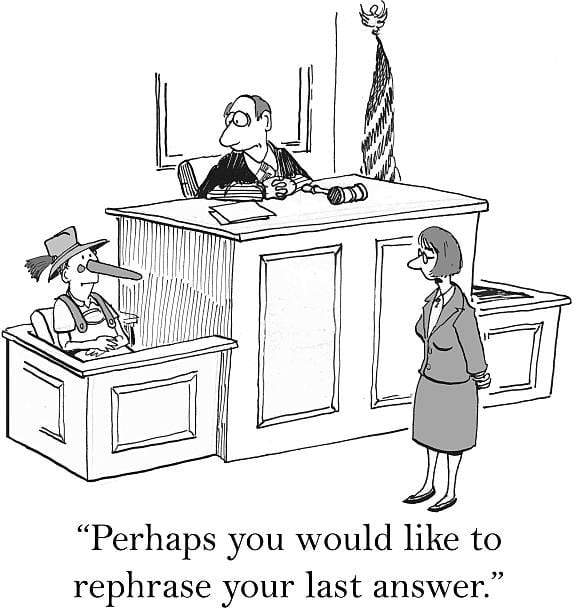

The expert witness sat in the arbitration hearing, confident in his technical analysis. His report was thorough, his credentials impressive, his client satisfied. Then opposing counsel asked a simple question during cross examination: "In your report, you state the mechanical coordination drawings were deficient at handover. If you had been instructed by the respondent instead of the claimant, would your conclusion about that deficiency be different?"

The pause that followed lasted only seconds, but the tribunal leant forward. The expert's technical opinions, though largely sound, suddenly carried less weight. The case turned not on engineering facts, but on a fundamental misunderstanding about what an expert witness actually is.

This scenario plays out regularly in construction disputes. The pattern is consistent: technically qualified professionals enter expert witness practice carrying a dangerous assumption that their job is to help their client win. This mindset creates significant credibility risks and separates inexperienced experts from those who build lasting reputations.

The Expert Witness Advocacy Trap

The confusion about the expert witness role is understandable. Lawyers advocate. Consultants solve their client's problems. So surely an expert witness does the same? The answer reveals a fundamental misunderstanding that creates professional risk.

Consider what happens during cross examination when an expert adopts a "help my client win" mentality. Opposing counsel presents a document that contradicts the expert opinion. An advocate would minimise it, reframe it, or explain it away. But expert witnesses testify under oath. The tribunal watches the response carefully. Does the expert acknowledge the contradiction honestly, or protect the client's position?

Choosing protection over truth signals to everyone in the room that the expert opinion is for sale. The tribunal may remain polite, but they have mentally downgraded everything the expert has said. Worse, the expert has handed opposing counsel a weapon to use throughout the remainder of testimony and potentially in future cases.

The Real Expert Witness Role: Independent Assistant to the Tribunal

Experienced expert witnesses understand a critical distinction: the real client is not the party that hired them. The real client is the tribunal, whether an arbitrator, judge, or adjudicator trying to understand technical issues outside their expertise. Whilst hired by one party, expert witnesses serve the tribunal's need for independent, reliable technical analysis.

This distinction matters in practice. When reviewing design documentation for MEP disputes, an advocate hunts for anything supporting their client's position. An expert witness examines the record to understand what actually happened, even when uncomfortable for the party paying the fees.

Cases often turn on moments when an expert witness acknowledges a weakness in their client's case. Tribunals notice intellectual honesty. They notice when expert testimony does not oversell. That credibility becomes currency when more critical expert opinions need to carry weight.

Professional Risk in Expert Witness Practice

Inadvertent advocacy in expert witness work is not always obvious. Common examples include:

Accepting the client's characterisation of events without independent verification

Focussing forensic analysis only on issues favourable to the client's case

Using absolute language like "impossible," "clearly," or "undoubtedly" when technical reality involves judgement calls

Failing to acknowledge legitimate alternative interpretations of ambiguous contract language or technical standards

Each move may seem harmless initially. Clients may even appreciate them. But experienced opposing counsel will expose these issues systematically during cross examination. Once independence is questioned, technical opinions lose force, even valid ones.

Take a common example: an expert reviews submittal drawings stamped "approved" by the design team and treats this as evidence that the installed work must be compliant. But approval of a submittal does not necessarily equal acceptance of the proposed installation method, particularly where the submittal was marked "approved as noted" or where site conditions changed. Adopting the instructing solicitor's interpretation of what "approved" means without examining the actual submittal conditions and correspondence is inadvertent advocacy. It assumes a conclusion rather than analysing what the contemporaneous records actually show.

How Experienced Expert Witnesses Think Differently

The shift in expert witness mindset is subtle but fundamental. This is the kind of judgement that is easy to understand in theory and much harder to apply under pressure. Before putting anything in an expert report, experienced practitioners ask: "Would this conclusion remain the same if instructed by the other side?" If the honest answer is no, the analysis has likely drifted into advocacy.

This approach does not mean neutrality about technical facts. If design documentation was objectively deficient, the expert report should say so clearly. If a contractor failed to follow industry standards, state it. But these conclusions must be framed as independent technical findings, not arguments crafted to support a predetermined outcome.

The practical result? Expert reports should be useful to tribunals even if they ultimately decide against the instructing party. Expert testimony should educate, clarify technical complexity, and acknowledge where reasonable experts might differ. It should never read like it was written by someone who forgot they are under oath.

A Brief Self-Check

Before finalising any expert opinion, consider these questions:

Would I reach the same conclusion if instructed by the other side?

What evidence could reasonably undermine this opinion?

Have I presented judgement as certainty anywhere in my report?

If any answer creates discomfort, the analysis likely needs recalibration.

Golden Rules Experienced Expert Witnesses Live By

Independence is not a posture. It shows up in small decisions. Language, tone, and what you choose not to argue matter as much as conclusions.

If an opinion only works for one side, it probably is not an expert opinion. Sound conclusions survive regardless of who pays the invoice.

Tribunals forgive uncertainty more readily than advocacy. Overconfidence is far more damaging than acknowledging judgement calls.

Your report should still make sense to the tribunal if your client loses. If it does not, something has gone wrong.

The moment you feel the urge to protect a position, pause. That instinct is the clearest warning sign of drift into advocacy.

The Expert Witness Paradox

Refusing to be a client's advocate makes expert witnesses far more valuable to them. Independence is not a liability in expert witness practice. It is the entire basis for why expert testimony matters in arbitration. Tribunals do not need another lawyer arguing the case. They need someone who will explain technical truth, even when complicated, uncertain, or unhelpful to one party.

Expert witnesses who understand this principle build reputations that last decades. Those who miss this distinction often wonder why they are not instructed again, why cross examination went poorly, or why tribunals seemed sceptical of opinions they felt certain about.

For professionals early in their expert witness career, this is the moment to examine instincts carefully. The desire to "help" a client win is natural, understandable, and professionally dangerous. The expert witness role is not to win cases. It is to help tribunals understand technical truth. Everything else follows from getting that distinction right.